Lee Burdette Williams

I’ve always said that the key to being successful as a student affairs professional is remembering what it was like to be 19 years old, which prompted me to keep a photo of myself at that age in my office where I could see it over the shoulder of any student with whom I might be talking. The world looked and felt very different to me then, and I knew it was important that I listen to my student through those 19-year-old ears and try not to judge them from my position as a woman well into middle age.

I’m 55 years old. I have worked for three decades in student affairs in a variety of roles, including as a senior student affairs officer. When I read the posts and comments and replies to comments and replies to replies on this page, it is very easy to view them through the eyes of a “seasoned” student affair professional (I’d like to point out that one can be “seasoned” in a multitude of flavors). It’s easy to be dismissive of, or roll my eyes at, what seems sometimes to be youthful indiscretion or anger or lack of perspective.

And then I remember myself as a young professional. This letter goes out to my peers—people in their 50s and 60s and beyond who treasure this profession like I do, who have done hard work throughout long careers, who have loved students and colleagues and stuck with them through hard times and good. Let’s remember. Can you join me on a journey backwards to yourselves as a young professional? I’d like to tell a few stories to help get you in the mood.

Once I stood in a parking lot arguing with a vice president who had made a decision I strongly disagreed with. I was not, I am certain, gracious about it. He listened and said, “I disagree with you, Lee, and I’m not going to change my mind,” and went on his way. I am certain—CERTAIN—that I returned to my office and griped about him. I am equally certain I was not discrete, because, well, I wasn’t in general a very discrete young professional. Another time I thought my institution was going to hell in a handbasket and shared that opinion with colleagues. Gracious? Not a chance. I was righteously indignant.

Thankfully, Facebook didn’t exist back then. When I think of the times I would have used it as a tool to express my frustrations, anger, doubt, and ego-driven certitude…well, let’s just say I would probably have never shut up. Luckily, my disappointment in colleagues, my employer(s), the world itself, was shared in much more limited ways. Which is not to say it wasn’t shared. My colleagues, professors and classmates would tell you that I was, to put it mildly, outspoken.

But what made it different then was that those same people responded to me personally, graciously, patiently, perhaps doing their own internal eye-rolling, but unfailingly treating me with respect. That respect is what we owe our younger colleagues who do have the tools of Facebook and other social media to express anger.

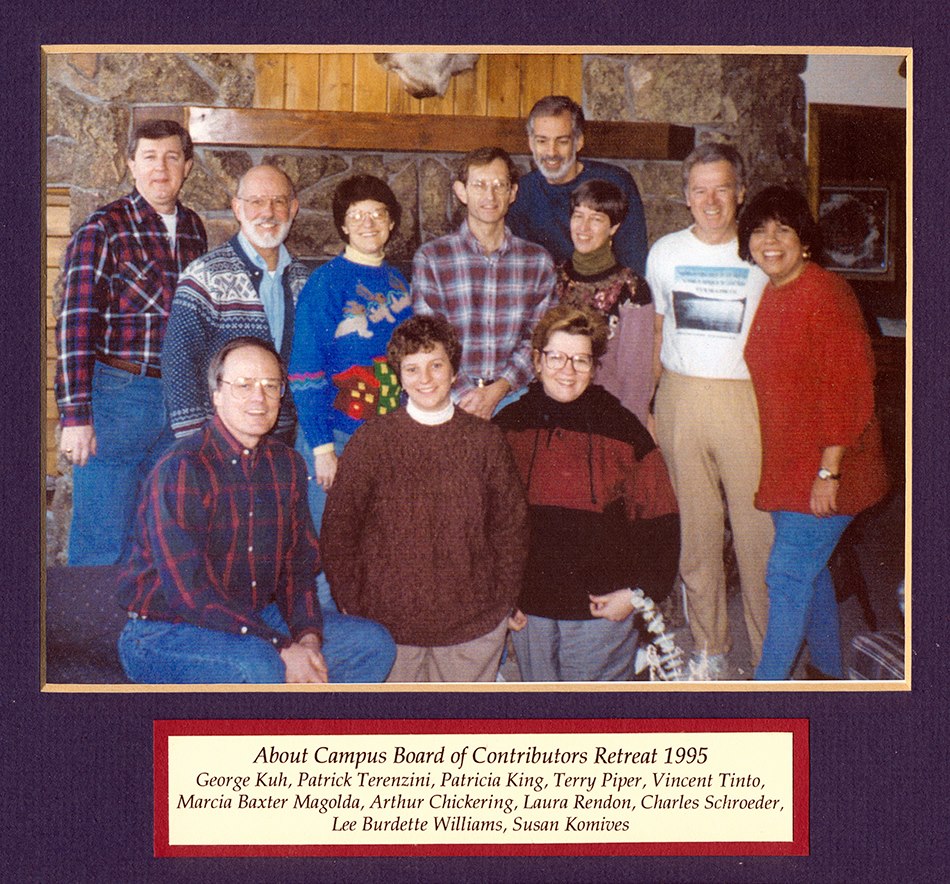

Another story: I was a young, newly-minted Maryland Ph.D., working as a student activities director at a small college in Michigan when, through magical thinking and the skill of the Human Rolodex of Student Affairs herself, Susan Komives, I found myself appointed a section editor of a publication about to be launched by ACPA, About Campus. The magazine, the brainchild of Charles Schroeder, former ACPA president and then-VP at the University of Missouri, was, however, on the verge of collapse without ever seeing the light of day when Charles swooped in and rescued it, keeping me in that role for reasons I never understood but was grateful for. Charles gathered a group of his long-time professional friends at a retreat at his beautiful mountain home in Estes Park, CO, in order to salvage the publication, which is how I found myself in the backseat of a rental car driven by Patrick Terenzini with Vincent Tinto riding shotgun. Me, a clueless young professional, shaking in my boots and kissing theirs, listening as they shared not their opinions on the state of higher education, but their own stories about getting into the field. We arrived at Charles’ house where he had gathered (I kid you not) Patricia King, Marcia Baxter-Magolda, Laura Rendón, Arthur Chickering, George Kuh, Terry Piper, Susan Komives, Terenzini and Tinto, and…me (here’s the photographic evidence--don't ridicule our sweaters).

I was so utterly out of my league. My then-colleagues teased me mercilessly for months afterwards that my contributions had included thoughtful statements like, “Can I refill that for you, Professor Chickering?”

This group included some of the nicest, most approachable people I’ve ever known. At dinner one night, Art Chickering turned to me and asked me what I thought about some emerging issue in orientation programs. I sputtered some response. And then refilled his coffee.

Throughout my career, I have been on the receiving end of some of the most gracious mentoring I could imagine, even in those moments when I probably didn’t deserve it. Another story: final year of my doctoral program. At ACPA, I found myself at a dinner with about 15 people who had participated in a pre-conference workshop that day. As the dinner check circulated, the group quickly agreed to split it evenly. I was mad. I was a grad student with an $11,000 annual salary. I had eaten only an appetizer and had drank no alcohol. I started to make some indignant noises when Sue Spooner, long-time faculty member at Northern Colorado, leaned over to me and said quietly, “Dear, in a group like this, it’s much better to just split the check evenly. I would be happy to cover your portion.” Mortified, I again sputtered: a quick “no thanks,” grateful for two lessons this kind person, who barely knew me, had proffered: splitting the check is what grown-ups do, and calling someone on their behavior is best done privately and with kindness.

I share these stories because I try every day to honor the many mentors who tolerated my anger, my indignation, my frustration with the way of things in higher education and student affairs. I always thought I had things figured out, and too often overlooked the fact that many of these people had been doing this hard, hard work for decades before I rolled along and started expressing my opinions to anyone who would listen.

I am grateful for professors like Susan Komives and Marylu McEwen who I am certain often questioned the wisdom of accepting me into that program. I am grateful for role models like Linda Clement and Dick Stimpson, who displayed the art of gentle correction with me more times than I can count. I have worked for three men, as different in temperament and background as possible, all of whom displayed to me the way you treat a young professional who is full of herself and impatient with others. Don Omahan was the most gracious man who ever held a VP title. Greg Blimling loved it when I pushed back on his thinking, and did the same for me. Ronald Crutcher, the only president to whom I’ve reported, demonstrated the kind of dignity that such a position calls for.

I have valued older professionals who have, throughout my career, taken the time to listen to me, to talk with me, to answer my questions—always in a respectful tone (I’m looking at you, Carney Strange, Leila Moore, Will Barratt, Kathy Manning, Kathy MacKay, Cynthia Cherrey—this list could go on and on).

I was blessed with classmates with whom I have moved forward in the profession, none of whom ever threw anything at my head in a classroom despite how appropriate it might have been at the moment (thank you Donna Talbot, Deb Taub, Donna Swartwout, Mike Freeman, Susan Jones, Linda Murphy, Jamie Washington, Jan Arminio).

And colleagues? Here’s another story. I was a vice president and dean of students when I found myself facing a very unexpected and devastating separation and, ultimately, divorce from my husband of 25 years. Without knowing what else to do, I just kept going to work. Every day I showed up and tried to immerse myself in the complexities of my job, focus on my students and staff, attend events, cheer on teams, and then go home and fall to pieces. I was, to use a word that’s been used on this Facebook page a lot lately, broken. It was weeks before I could even share with people at work what was happening, and since I lived in campus housing, that wasn’t an easy secret to keep. I’m sure I wasn’t at the top of my game, but those folks propped me up on bad days. I pondered a departure, more from the home I had shared with my husband and less from my job, but they were a package. I applied for a VP position in another state and ended up a finalist. I heard from someone at the institution that the president was very enthused about my candidacy. It was the exit I thought I needed.

I sat in the office of my closest friend, Provost Linda Eisenmann, and told her this news. She asked if I wanted her advice. Of course. She said, “You need to stay here right now. This is not just self-interest, though I would be sad if you left. We have so often talked about how hard it is to be new someplace” (we had started on the same day three years earlier). “I think what you need right now is to be around people who know you and love you and will help you heal.” I had trusted her at every other point in our relationship. I went home and emailed the president of the other institution, withdrawing from the search.

I stayed for another three years, and she was right. Being around familiar and supportive people helped me heal. What I learned, and still learn every day is that when you are broken, and you heal, you’re a different shape, a different person, and who that person is has a lot to do with the people around you.

It’s hard to share that story because there are things I’m pretty private about, but it’s been instructive to me, a reminder of what I value about working in higher education. The field attracts good people. Not that there aren’t some truly difficult and ugly people who end up in these jobs, but percentage-wise, this is a profession of caring and committed people. And the people I’ve valued most are the ones I’ve seen every day. That’s the community that needs the most attention, patience, love, respect. If I could say one thing to those who have said that Facebook offers them their most significant community, it would be this: don’t give up on the people around you. When you find yourself on a medical leave following surgery (and I speak from experience), they are the ones who will show up with hot meals and magazines.

When I think back to my earliest days in the field, I see us as a profession that was not diverse enough, but working to get there. “Social justice” was not as common a term, but the work was being done. We called it “multicultural competence” and “diversity programming” and we sometimes met with what we felt was resistance from our older colleagues. Some of the eventual canon of social justice work, though, was being crafted in those days by people like Raechele Pope, Amy Reynolds, Nancy Evans, Michael Cuyjet and others working to find the language we would need to move forward. We had Sedlacek’s Non-Cognitive Variables and Bernice Sandler’s “micro-inequities” and Peggy McIntosh’s invisible knapsack of white privilege that we were constantly trying to unpack—all roots of current social justice literature. Heck, ACPA’s Standing Committee was only “LGB” when I first became a member, and the “B” was seen as edgy. We have come a long way.

If one looks around at our profession now and sees it for the diverse community it is, perhaps that’s because the work that was done by those who were on the front lines during the 1970s, ‘80s and ‘90s accomplished something. We griped about the old white men in senior positions, but look at the evidence in our field. Look at NASPA, an organization that once tended to those very men, now thoroughly committed to supporting the social justice work of its diverse membership. Some good work was done, and while it would be nice if our young colleagues gave us some credit, that’s just not the way the world works. We didn’t give our elders much credit. We felt like we were out there on the battleground alone. And yet, changes happened that could not have occurred if they weren’t listening.

If you are, like me, one of those over-50 SA pros who regularly lurks on this Facebook page and occasionally wonders what has happened to our profession, I offer this: we happen. Those of us who occupy these jobs, whether it’s residence hall director or academic advisor or conduct coordinator or professor or dean or vice president—we are the profession. None of us own it. We rent it, having been given it in trust by those who mentored us, cared about us, taught us, gently corrected us. We keep it safe and hand it to those who come after us, and who deserve the same mentoring, care, teaching and gentle correction. We no doubt baffled and irritated our elders as young professionals, but think about the role models who mattered to you, and how they treated you. Offer that to our young colleagues, modeling at every opportunity that the river that flows through student affairs is still shaped by our founding documents: every individual has worth and dignity.

If any of you young pros are still reading: Thanks for all that I have learned from listening in on the sometimes difficult discourse. No, I don’t post much, but I’m paying attention and while I may be old—ancient to some of you—I know I still have a lot to learn. In your honor, I am going to replace that picture of my 19-year-old self with one from my earliest professional years so I can try, on a daily basis, to recall that passion, those deep emotions, that impatience and frustration, and when I see it in you, know that it is what student affairs has always needed, always had, and will continue to require.